Written by Jeffrey Stanton with roller coaster revisions by Patrick McKinney

The property that eventually became Olympic Park was purchased by John A. Becker, an affluent member of Newark’s German community. In December 1868 he purchased a small farm on Boyden Avenue from his father-in-law. Becker was captivated by the area’s wooded beauty surrounding his farm that he eventually purchased the surrounding wooded property.

In 1872 the Mutual Homestead Association, acquired 25 acres of farmland adjacent to Becker’s Woods to develop a housing tract of 170 sites. Becker, at the time, was president of the German organization which encouraged home ownership. Since the residents like to picnic in the nearby woods, Becker cleared a few acres and turned his woods into an amusement park. The park opened on May 8, 1887 with a nine-pin skittle bowling alley, rifle range, swings for the youngsters, an dancing pavilion and a saloon. The later in a one-story framed building was kept stocked with beer and wine. A small string band provided music for dancing. Becker’s son William managed the park for the first two seasons and built a baseball field.

Frank Buehler, who owned the German-American Brewing Company and the adjacent Germania Hall beer garden in Newark, leased the park for the 1889 season. However, after he was arrested for violating the Sunday law against selling liquor, he was forced to close the saloon, the park’s only money maker. His associate Louis Ort, took over the park for the 1890 season.

In 1897, Frank Buehler, Louis Schultz and Gustave A. Grub leased the park for the Becker heirs (Becker died in 1892) and renamed it Hilton Park. In 1899 they added a second ball field and bowling alley, enlarged the restaurant and added electric lights. Sacred concerts were scheduled on Sundays, but the musical offerings were varied from military bands to opera. Reaching the park was easier since the Irvington and Hilton trolley stopped directly opposite the park entrance and only cost a nickel from downtown Newark.

Hilton Park was one of the few amusement parks without mechanical rides in Essex County. The public didn’t seem to mind for they flocked to the park for its beautiful woods, grassy fields, soothing music, its delicatessen, and foamy steins of beer.

But times were changing and young people didn’t like the genteel Victorian ways of their parents. Once the mechanical rides at Coney Island in New York excited the public, they clamored for a similar exciting experience in their local parks throughout the nation. Newark was no exception and on Memorial Day 1903, Electric Park opened for business on South Orange Avenue in Newark. It featured a carousel, toboggan slide, old Mill ride, a dancing pavilion, open air theater, a menagerie (zoo), and an electric fountain, which gave the park its name.

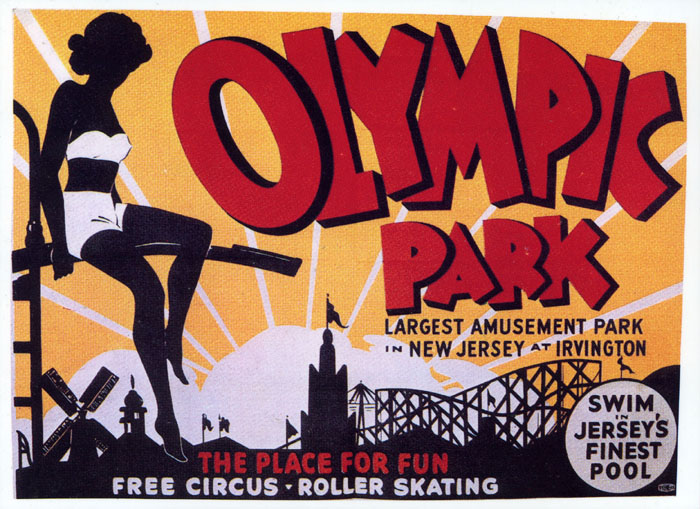

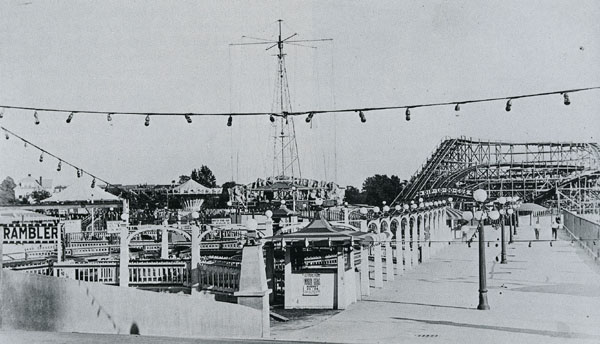

To compete, Hiton Park was turned into a mechanical amusement park and renamed Olympic Park. It opened on May 28, 1904. Herman Schmidt, a 44-year-old businessman and his brother-in-law Christian Kurz, who owned a popular Springfield Avenue restaurant and beer garden, poured $20,000 into the venture. The park was named in honor of the Olympic Games held that year in St Louis. Its new imposing entrance with is four huge pillars had an electrified sign with the park’s name hung from the overhead arch. Just beyond were two large lion statues. Two thousand electric lights illuminated the park’s dense foliage and midway at night.

Entrance to Olympic Park

Lion Statues just inside the entrance

While the initial midway was small even for parks at the time, it featured a 20-foot-high Helter-Skelter spiral slide, a Moorish palace style fun house, swings, gypsy fortune tellers, and camel and pony rides for the children. The immense dancing pavilion was finished several weeks after the season began. Management’s emphasis was on family attractions that appealed to every age group. Space at the old baseball field was allotted to the circus, which was booked for the entire season. Astonishing acts performed in the arena included Blondin, the Human Torch, who jumped enveloped in flame from a platform 75 high into a four-foot-deep tank of water, and Professor Alfreno, the High Wire King, who while carefully crossing the lofty gap, ignited fireworks attached to his costume. Other acts included the Mohrens, trapeze artists, Kenyon and DeGarmo, gymnasts and balancers, and Raymond the human pinwheel.

Spiral Slide

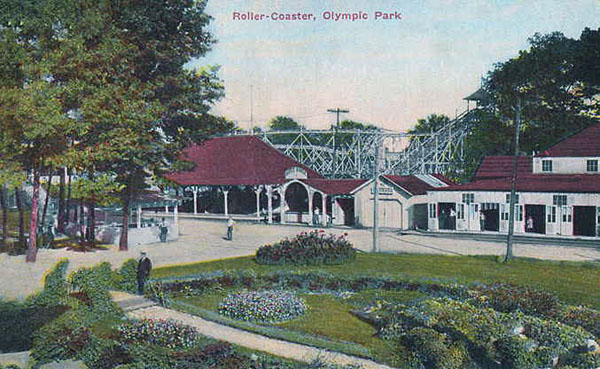

After a successful 1904 season, Schmidt and Kurz began planning a more ambitious expansion of attractions. A new ballroom, theater and restaurant were built at a cost of $45,000 with an additional $11,500 for electric lighting and landscaping. The new theater could seat 2500 people and the two-story dining pavilion had 400 tables. They erected a roller coaster, shooting gallery, large merry-go-round, a menagerie of animals and a playground for children. Afternoon and evening vaudeville performances were given in the theater. It was a mixture of comedians, animal acts, and a man named Leo Dervalto, who mounted a revolving globe and walked it up a spiral incline, 33 feet in height. There was a also an electrical illusion show called the Fall of Port Arthur, a Russian military base that fell to the Japanese Imperial fleet the previous year.

View of park showing Figure-8 coaster

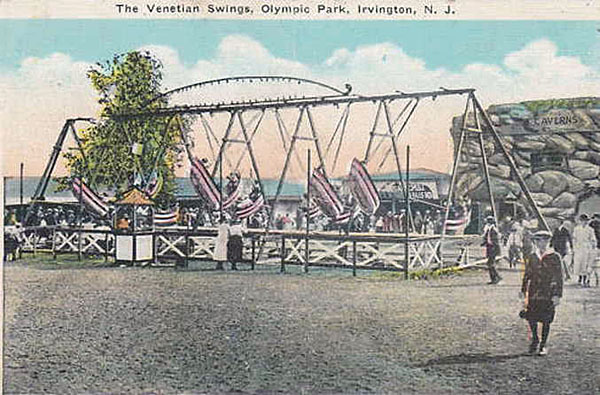

Venetian Swings and Caverns attraction

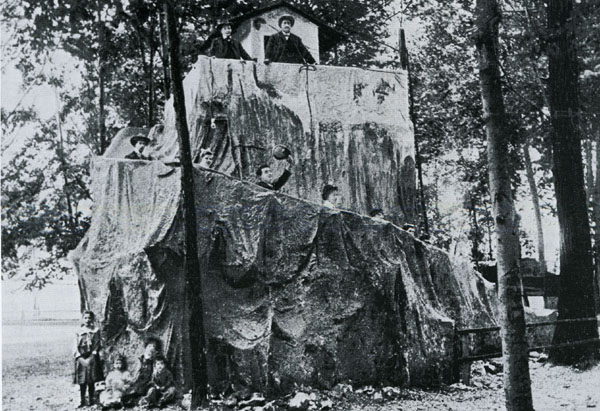

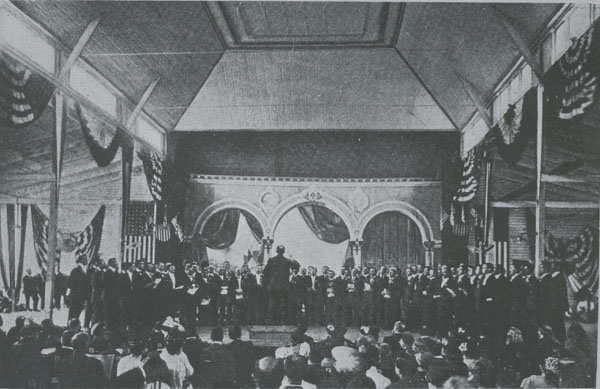

The park’s popularity with Newark’s German-American population led to its selection as the site of the 21st National Saengerfest for the northeast to be held July 1-4, 1906 Every three years German singing societies from New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland and Delaware celebrated “the charm of German music and song.” Schmidt built a wooden concert hall 90 x 160 feet, and erected scores of tents that served as headquarters for the various singing societies.

The four day festival drew 5000 singers from a hundred organizations in 40 cities. Chartered trains brought 700 from Baltimore, 1000 from Philadelphia alone. Five thousand jammed the new concert hall, more than half who stood along the walls and in the aisles, to hear the New York Philharmonic led by Julius Lorentz, the festival’s music director. The Hymn of Welcome, written for the festival was sung by a male chorus of 560. The festival drew 25,000 to the park daily.

1906 Saengerfest stage

A camp full of large tents were set up at the far end of the grounds. Each singing group was assigned a tent festooned with the group’s banner, a long table and rows of empty beer steins. The casks of beer were stored on ice in two large depots, and when one cask was empty, another would be brought to the tent as oceans of beer were consumed. As evening approached, the Saengerfest became a singing festival with each group singing songs and melodies from the Fatherland. As the evening wore on and the alcohol took effect, men and women formed lines and marched down the city of tent’s streets saluting and serenading their fraternal brethren. After the Kaiser prize was awarded on the last afternoon, the festival officially closed.

By the sixth season in 1909, the park’s popularity made it the favorite of Essex County’s pleasure seekers, far ahead of its competitors Hillside Pleasure Park and Electric Park. Its success was due to Schmidt’s talent in attracting “a better class of customers,” who flocked to its opera house, dining and dancing pavilions. There was a strict dress code in the park where men weren’t admitted without a coat and tie, and children were expected to wear their Sunday best.

The park’s 400-table restaurant had a seating capacity of 1500. It offered full course dinners from 25 to 75 cents. Its specialty was seafood and its reputation was such that it attracted visitors from Newark, Jersey City and even New York City. They arrived by carriage or automobile for a full night of fine dining and dancing. Its clambakes were famous, and when the opera was in season, the restaurant featured cabaret entertainment. Upstairs, above the restaurant was a large dance hall that charged a penny a dance. Couples danced to the music of Herman Handister’s Orchestra.

Dancing Pavilion

Perhaps the park’s greatest draw before the first world war that attracted a wealthier class of patrons, who appreciated high-culture, was the Aborn Opera Company, owned by Milton and Sargeant Aborn. Performances began in July 1906 at the Olympic Park Theater, a large, semi-rustic, open-air playhouse seating nearly 1000, that was built especially for the troupe. It featured a spacious stage and the latest in theatrical equipment to present the light opera performances held there on Saturday and Sunday afternoons until 1920. The most popular were the light operas by Gilbert and Sullivan, Victor Herbert, Oscar Straus, and George M. Cohan. Their shows like The Mikado, Pinafore, Carmen, Fra Diavolo, Die Fledermaus, When Johnny Comes Marching Home, Bells of New York, Madame Sherry, and Little Johnny Jones were favorites that drew repeat customers. The light operas had become so popular that after the North Eastern Saerigerfest ended in .Iuly 1912, the 2,500-seat concert hall erected for the festival was converted into an opera house.

Free music was always an integral part of the park Schmidt booked famous concert bands led by John Philip Sousa and Arthur Pryor. Schmidt’s nephew led the nine-piece Olympic Park Concert Orchestra began playing at the park in 1911.

Aborn Opera Company

Schmidt, always seeking acts that would pull in crowds, signed many of the best entertainers of the era. Free afternoon and evening vaudeville on the park’s open-air stage was a park tradition, with Schmidt hiring 1000 different acts during a twelve year period. Each show consisted of between eight and twelve acts and lasted an hour, the limit that one could stand since there were no seating. It featured a combination of animal acts, acrobats, dancers, comedians, dancers, strongmen and various circus performers. One sensational act in 1906 was a pair of Arabian horses trained to dive 30 feet into a pool of water. Comedian Mae West, before her motion picture days, performed at the park one summer. And when motion pictures became popular, the evening vaudeville shows concluded with 10 minutes of newsreels and comedy shorts, then a fireworks finale.

In 1909 Schmidt completed a half mile horse racing track and grandstand. Harness racing was held weekly from 1909 to 1914. When the Essex County Speedway closed in 1911, the horse racing association moved their races to Olympic Park. Motor cycle racing also shared the track beginning in 1909. It was good for park business since the races drew large crowds who stayed afterwards for an evening of dining and dancing.

In 1912 the park reported in Billboard that they had a Wild animal arena, a trick house, crystal maze, miniature railroad, carousel, razzle dazzle, pony track, figure-8 roller coaster, and a Wild West show.

Harness Racing at Olympic Park's race track

Olympic Park - 1912 Map

Schmidt’s years of operating the park successfully suffered a catastrophe as the 1914 season began when the opera house burned to the ground on day the opera season was to have begun. The fire was discovered shortly after midnight when flames erupted from the theater’s rooftop. Despite the heroic efforts of the firefighters and the park’s employees, the building was consumed within an hour. Flying embers set fire to the roof of the dance pavilion and grandstand and it looked like the entire resort would perish. Schmidt lapsed into a coma during the height of the fire, and when he regained consciousness, he was unable to speak. The $50,000 loss was only partially covered by insurance. The building was rebuilt within a month, but sadly the opera never regained its popularity.

With disastrous summer weather affecting attendance, the park debt rose to $90,000 by August. A month later a committee representing the park’s largest creditors took over the management of the park. The string of bad luck continued into the fall, when seven straight rainy days turned the County Fair held at the park into a fiasco. Then in December 1914 the County Prosecutor banned prize fighting, the park’s most popular post season attraction since 1912. During the next ten months Schmidt tried desperately to raise enough money to pay off his creditors. In the end he lost the park in a sheriff’s sale on August 6, 1915. The Home Brewing Company was the high bidder at $55,000. They announce that the park would reopen the following spring.

Henry A. Guenther, Home’s general manager, hired Christian Kurz, who had sold his share of the park to Schmidt several years earlier, to manage the Olympic Park. Fifty thousand dollars worth of improvements were planned. But despite Kurz’s best efforts he couldn’t attract the park’s traditional large crowds. Less than a month after opening, he committed suicide in June 1916. Rather than take a loss, Anthony J. and Henry A. Guenther, Home’s principal stockholders were compelled to take a more active role in managing the resort. They soon discovered that they enjoyed running the park and as astute businessmen made a success of it. After the nation passed Prohibition Amendment in January 1919, they bought the park from Home Brewing for around $100,000 on September 24, 1919. The 1920 season was the last to follow the Schmidt formula with free vaudeville and, the Aborn Opera Company.

The roller coaster was leased to Tom Kerstetter of Washington, D.C. for the 1919 season. He also added a whip and Ferris wheel. The park also opened a new Penny Arcade, a Kentucky Derby game, and a circle swing. One of the big attractions for the 1920 season was Bostock’s European Circus, with a roster of wild animal acts that included ferocious lions and tigers, Burgess's six performing goats and Baynor's dogtown cabaret, "consisting of 15 singing, dancing, acrobatic, mind-reading canines.

Ice Cream pavilion - 1920

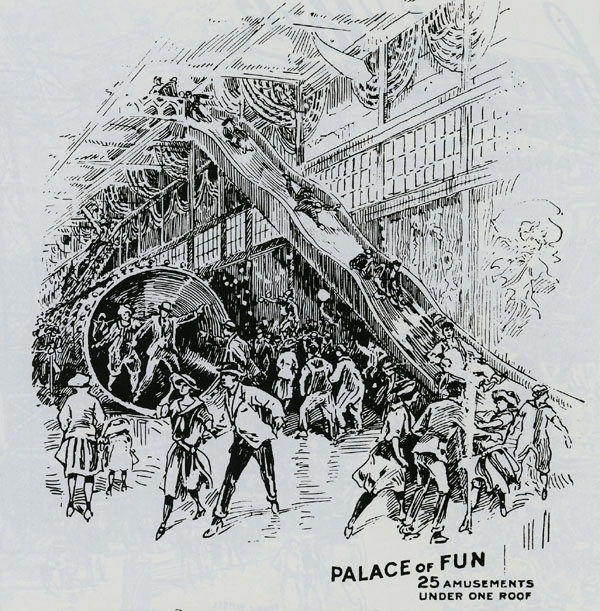

With Prohibition in effect, Guenther decided to convert the park into a non-alcoholic amusement park in the tradition of Coney Island with a gate admission of only ten cents. The C.S. Rose Company of Baltimore converted the former opera house at a cost of $50,000 into a fun house for the 1921 season. The park’s Palace of Fun with its 25 attractions, modeled after Steeplechase’s Pavilion of Fun, became the park’s centerpiece. Inside were various fun house devices like a revolving barrel, a high alpine slide, a revolving social mixer that spun patrons off into the surrounding catch basin. Other devices included a wiggle-woggle, the squeezer, the barrel chain and a haunted castle. Admission allowed one to ride as many attractions as one liked and children could spend the entire day inside for one low admission price.

Palace Fun House - 1921

Billboard magazine reported in February 1921 that the park had hired Vernon Keenan to design a new roller coaster called ‘The Caverns’ for lessees T.E. Kerstetter and Jacob Axelrod of New York. ‘The Caverns’ may or may not be the same as the ‘Deep Dips’ coaster listed in a Miller & Baker 1923 brochure as built within ‘the past three seasons’ (1920-1922). ‘Deep Dips’, in turn, is very likely the same as the first ‘Jack Rabbit’ coaster since available views show the early Jack Rabbit to be of the same character as an early ‘20s Miller & Baker ride, and no other coasters have yet been visually identified which could be from the same period.

It should be noted that Eric Siegal’s book ‘Smile: A History of Olympic Park’ states that the Jack Rabbit was built in 1926, but this date is likely wrong since, as already mentioned, the Jack Rabbit is consistent with an early ‘20s coaster. Siegal’s date may refer either to a refurbishment of the ride, or to the opening for the relatively nearby Palisades Park ‘Skyrocket’ instead.

The park retained some of the popular older rides like the old mill, carousel, whip, figure-8 coaster, aeroplane, frolic, miniature railroad, witching waves, and Ferris wheel. New rides included a dodgem bumper car. Weir’s jungle of performing tigers, lions, bears, birds, and monkeys was a popular show inside large tent.

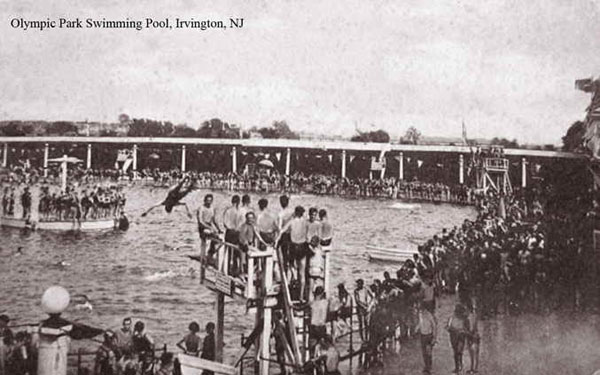

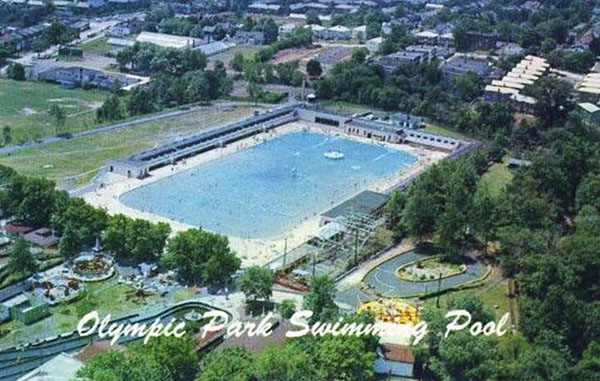

Olympic Park needed an Olympic-size swimming pool, but the various park owners lacked the capital to built one. The Guenthers even advertised in Billboard Magazine in 1919 seeking a concessionaire, but there were no takers. Finally in 1922 a group of enthusiastic New York investors formed the Olympic Natatorium Corporation and signed a twenty year lease with Guenther. It was headed by Sidney Reynolds, president of World Wide Amusement Company, John O’Brien, associated with Amusement Builders Corporation, and John R. Walker, a businessmen. By promoting the pool’s investment potential, they sold $220,000 worth of stock, mainly to small investors in Newark and Irvington. The investment entitled one to a share of the profits and twenty years use of the pool at no cost.

Construction of the pool began on February 19, 1923 when they began excavating 26,000 cubic yards of earth and rock from the area of the park that had been a racetrack.. The pool was mammoth; 400 feet long and 200 feet wide with a depth ranging from 9-1/2 feet to less than a foot, holding 3,750,000 gallons of filtered chlorinated water, and could accommodate 4000 bathers at one time. The pool’s sides and bottom required 4,800 barrels of concrete, and took four and one half months to complete. The job also required 11 miles of pipe for water, gas, electric and sewage lines, and the installation of 7000 lights for night bathing. In addition there were 1000 individual bathhouses and 3000 lockers and above it a series of bleachers seating 5000 people, that formed an amphitheater around three sides of the pool. And at the shallow end of the pool a sea swing was installed. To create a sandy beach 165 feet long by 135 feet long, they imported 18,050 tons of sand from Rockaway Beach, NY.

It took ten days to fill the pool for the opening on July 4, 1923. The highlight was a water carnival that starred world champion swimmer Johnny Weismuller , his brother Peter, and Getrude Ederle and Aileen Riggin of the New York Woman’s Swimming Association. They all competed in 50 yard and 300 meter races. However, the scheduled diving completion was cancelled since the pool was only three quarters filled because the water company would only allow the park to fill the pool at night.

Olympic Park Swimming Pool - 1923

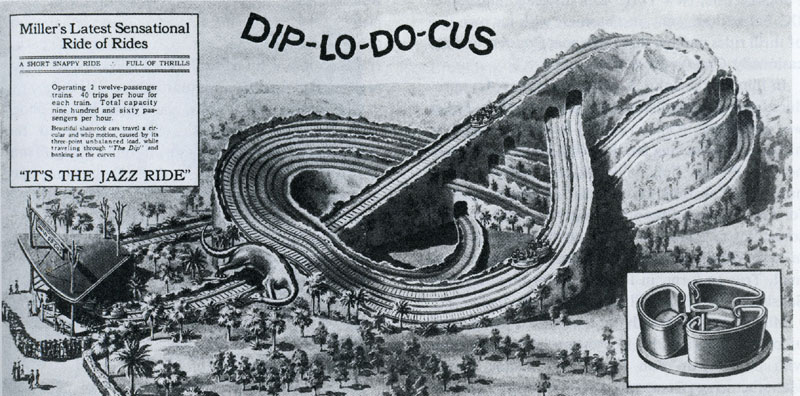

By 1923, the novel ‘Dip-Lo-Do-Cus’ rollercoaster was in operation at the park. John Miller had invented this unusual ride model with the intention of retrofitting his older coasters in order to revive their popularity. The ride’s novelty came from the use of rotating, circular ‘shamrock’ cars, each of which arranged three two-passenger couches around its perimeter, producing an unbalanced distribution of weight which, in turn, encouraged the car body to revolve on its mounts as it travelled over the undulating figure-8 course. Operating experience, however, revealed that the weighty cars placed excessive stress on the structure, and this issue likely doomed the type’s appeal with any new buyers.

The name Dip-Lo-Do-Cus came from an 84-foot-long dinosaur exhibited in the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, and this is corroborated by a conceptual drawing showing the use of painted sheet metal on the ride’s structure depicting the dinosaur’s pre-historic habitat. It isn’t known whether Olympic Park’s ride was ever actually covered in this manner as all available photos show only the usual exposed coaster structurework. Another disputable feature of Olympic Park’s ride is revealed by a plan shown in Robert Cartmell’s book ‘The Incredible Scream Machine’. The plan, which the author dated to 1924, is of the Olympic Park Dip-Lo-Do-Cus, but with the name ‘Whirlwind Ride’ used instead. This could be the original plan with the name being the one originally intended for the ride model, or the plan could have been made to show modifications to the existing ride. Whichever may be the case, no other available photos or materials show operational use of the Whirlwind name. (If anyone knows or has better photos, please contact Jeffrey Stanton.)

Drawing of Miller's Dip-Lo-Do-Cus roller coaster

.

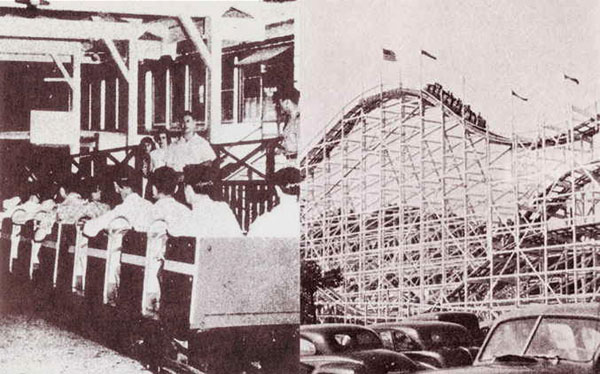

Jack Rabbit roller coaster

View

Midway & Dip-Lo-Do-Cus roller coaster

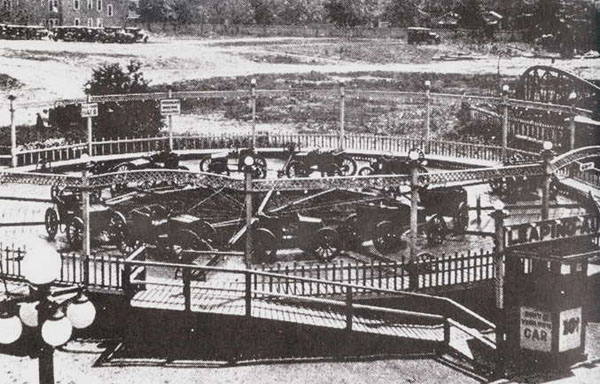

The Leaping Lena ride, a rearing. Leaping auto ride that circled the platform debuted in 1926. There was also a new Traver Tumble Bug, and a Hey Dey rides and an attraction called a Trip to Paradise. Venetian swings were for adults and baby swings for children. Custer cars, with 3 horsepower engines that propelled the self driving cars on a serpentine course at 5 MPH was also added. A Caterpillar circular flat ride whose retractable canopy covered the riders, was popular with couples because they could kiss without being seen. The 18 hole miniature golf course was added in 1927, long before the fad peaked in 1930. New that season was an alligator show.

Leaping Lena Auto Ride

Bluebeard’s Castle debuted for the 1928 season. It was a horror-themed fun house based on the Bluebeard legend of a man who murdered a number of wives in succession. Its entrance and exit was through the mouths of Bluebeard's giant heads flanking his notorious castle. Inside, beyond the gruesome reception room, which sent chills up visitors' spines, were narrow passage ways connecting rooms of the castle, each with trick floors, revolving disks, tread boards, mirror maze, air jets that blew ladies' dresses upwards and men's hats off. There were bypass areas for those who preferred to watch. Near the exit was the chamber of horrors, a room where decapitated woman's bodies hung and heads were stored on shelves, relics of Bluebeard's gruesome love affairs.

New shows included Frank Rupert’s Wax Show and Docen’s Freak Animal Show. The later had dozens of freak animals like pigs, sheep and cows with extra legs and even several two-headed animals. They were all alive.

Olympic Park’s first Mardi Gras celebration was held between August 27 to September 3, 1928, Labor Day. Modeled after Coney Island’s celebration, it was designed to combat the late August summer blahs. The park was decorated with strings of colored lights and carnival bunting, and the concessionaires wore outlandish costumes. An afternoon parade opened the festivities, and parades each night drew crowds. A masked ball featured the crowning of the queen. There were baby and doll parades, pie and watermelon eating contests, best costume competition, and a bathing beauty contest. $5000 in prizes were awarded during the week. Mardi Gras lasted at least through the 1931 season, if not longer.

Olympic Park was thoroughly overhauled for the 1929 season. The park’s two roller coasters, the Jack Rabbit and Dip-Lo-Do-Cus, as well as the Custer cars were variously altered. In the case of the Dip-Lo-Do-Cus, the Philadelphia Toboggan Company supplied a new set of standard type three-bench cars to replace the structurally punishing ‘shamrock’ cars. This required some track modifications for proper functioning of the ride. Other additions this season included a pig slide and upside-down house for the fun plaza, a modern Scrambler ride, and a large sports stadium.

Olympic Park - 1929 Aerial

PTC#46 Carousel - 5 Abreast with 4 ouside chariots

Olympic Park - 1930 Map

Early in the Depression in 1931, Olympic Park’s rides were divided up in two main areas. The upper level of the park far beyond the entrance had a Pretzel dark ride (installed previous year), Bluebeard’s Castle, the Custer auto ride, a Ferris wheel, Whip, Dodgem bumper cars, Jack Rabbit roller coaster, Old Mill, merry-go-round, miniature golf course, and a penny arcade. The lower level of the park (a drop of about 6 feet via a ramp) near the swimming pool, had a chair-o-plane, pony ride, Tilt-a-whirl, Lindy Loop, circle swing, Dip-Lo-Do-Cus roller coaster, Trip to Paradise, Frank Rupert’s Wax Show, 1001 Troubles glass house, Tumble Bug, Hey Dey, Cuddle-Up, Leaping Lena, Upside-Down House, an Illusion show, a Flight Tudor, Archery Court, and a small Kiddieland.

When the Depression began after the 1929 stock market crash, it rapidly spread throughout the country as factories laid off workers and 50,000 people were on relief in the Newark and its suburbs.. By 1933 area payrolls were at 45% of their 1925 levels and few had spending money for amusement parks. Olympic Park’s revenue was down 10% in 1931, and dropped a further 25% in 1933. Guenther tried to attract customers with inexpensive attractions like a bathing suit revue and many Three-Cent Days. John Philip Sousa and his band on August 25th also drew huge crowds that year. It was his fourth and final concert at the park.

Guenther hired a California Frank’s Rodeo for 10 days in 1932. They held walkathons in the dance hall during the 1932 season. They were musical endurance contests where dancers dragged themselves around the ballroom for 3,500 hours until only one couple out of the 58, who entered the contest, remained. Of course there were 15 minute rest periods each hour for eating, resting and bathroom breaks, but they danced day and night. When they became exhausted, one of the couple would hold the other up as they shuffled around the floor while his or her partner slept. The promoter, who offered cash prizes of $2000 for the top five couples, earned his money by selling tickets (a dollar on Friday and Saturday nights, less on weekdays) to spectators, many who came daily to cheer for their favorites. But there was to be no prize money as the promoter skipped town on the last day in February 1933. With the dancers were stranded without money or lodging, a benefit dance was staged to pay for their train fare home.

A second dance marathon opened on January 23, 1935 that was exceeded by comedian Red Skeleton, who poured soda pop over his head from 8:30 PM to 2:30 AM each night. It was much more successful, with two couples getting married during the ordeal. But there was also a pair of teenage girls in the audience, who tried to commit suicide by swallowing iodine.

Guenther erected a huge tent for bingo games in 1933 that featured prizes like bags of groceries. The Miss New Jersey beauty contest was held in 1933. Pool admissions prices were lowered, but the little helped as the 1934 season was the worst in the park’s history.

By the mid-‘30s, Olympic was forced to consider upgrades to its attractions in light of the growing competitiveness of Palisades Park in Cliffside. Palisades had always featured a lengthy roster of coasters and other attractions kept periodically updated, but this had been of little concern to Olympic Park in past since most of Palisades’ patrons were drawn from all around the densely-populated lower Hudson area, and here Palisades also had more direct competition from Columbia Park in North Bergen. But now, with the ever-present depression taking its toll, several Palisades competitors, Columbia Park among them, had shuttered and the surviving parks were forced to draw their patronage from farther and farther afield. As a result, Olympic Park’s modestly-sized decade-old coasters were now facing the superior drawing power of larger, newer rides at Palisades. Ultimately, Olympic rectified this shortcoming in 1937 when it replaced its two lacking coasters with a single, 80-foot tall ride built on the same site and bearing the same name as the Jack Rabbit.

The second Jack Rabbit was indeed an all-new ride since photos show it was sufficiently different in size, layout, and structure to make it impractical for anything beyond raw lumber or equipment to have been retained from the previous coaster. That said, there is a general resemblance between the two Jack Rabbits, though this mainly stems from lot constraints and the abandonment of the big diving turns in twisters due to depression-era maintenance woes. Though the confusion between the two Jack Rabbits has effectively foiled popular sources for designer/builder attributions, comparisons with other contemporary rides show that the newer Jack Rabbit was of the same make and model used at the time by ride designer Vernon Keenan of Harry C. Baker, Inc.

As America prepared and eventually entered World War II in December 1941, the area’s factories reopened and provided people with more spending money. There was gas rationing, but trolleys still ran to the park and attendance began setting records. But with so many men being drafted for the war, keeping the park running presented problems. There were plenty of old men available, but hiring high school kids to fill jobs was a problem. And with so many food items on the ration list, food stands could operate on a limited basis and items like popular roast beef sandwiches were not longer available. It was difficult to repair rides and buildings as building materials and parts were unavailable. Soldiers on leave, who entered the park for free, monopolized the shooting gallery until ammunition was no longer obtainable. The 1944 season debuted two new shows. The Cavalcade of Wonders was an illusion show, and Ethel Purties motordrome amazed spectators when she rode a motorcycle around the steeply banked track with two lions in the sidecar. By 1945 when attendance hit an all-time record, 105,000 people attended the 4th of July fireworks, the first in years.

Ethel Purties & her lion ride in a steeply banked motordrome

Kiddie Land

Miniature Railroad - 1949

Olympic Park - 1949 Map

The city of Irvington in 1951, enforcing the state’s anti-gambling laws, banned wheels of chance in the park. The 19 wheels, however, accounted for 40% of the park’s business. Fortunately only about half of the park was in Irvington, the rest were in Maplewood. The city confiscated the bagatelle machines on June 22, and prompted Maplewood to enforce the laws, too. The clever concessionaires replaced their wheels of chance with Stop and Game machines that had a large numbered board with lights. Up to 16 players at a time pushed buttons to stop the machine at what they guessed was the winning number. Irvington officials threatened to shut down the popular games. A restraining order was issued by the Superior Court until their legality could be proved in court. A college math professor testified in court in January 1953 that the game required both mental and physical dexterity. Olympic Park could keep their games. But that wasn’t the end of the fight for legality as the New Jersey State Supreme Court banned all games of chance in 1956. Games of chance didn’t return until voters approved skill games in a state-wide referendum in 1960.

On November 25, 1950, a hurricane with gusts up to 108 MPH caused approximately $125,000 in damages to the park, much of which resulted when large portions of the Jack Rabbit roller coaster were toppled to the ground. By February of 1951, the park had tasked the Philadelphia Toboggan Company with rebuilding the ride to the plans of the company’s President and Chief Designer Herbert P. Schmeck. Schmeck, however, was hindered in his work when a full set of plans for the existing ride could not be found among the medley of design and maintenance drawings the park kept. This complicated the marriage of new construction with the surviving 40% of the original coaster’s structure, reuse of which was desirable in keeping costs down. In the end, Schmeck was forced to do a make-shift job of structural integration for the initial opening, and return post-season to make the work seamless.

The rebuilt ‘Jet’ coaster opened June 9th of the 1951 season. It had cost $100,000 for Schmeck to recreate the coaster in a near-facsimile design, though further work in the fall, which saw the old portion of the ride completely rebuilt, would push the total cost even higher. Improvements over the old ride included slight increases in height and speed, the latter of which was possibly helped along by the chief new feature of the ride – a semi-fan-turn following the dip off the lift. Other than a slight change of name to ‘Jet Star’, the coaster would operate unaltered from this form, until the park’s closing.

Hurricane dameage to roller coaster November 1950

A list of the park’s rides and attractions that appeared in Billboard in 1952 included: a roller coaster, whip, cuddle-up, Ferris wheel, dude ranch, donkey ride, Twister dark ride, pony track, auto skooter, caterpillar, auto speedway, octopus, U-drive motor boats, Looper, Airplanes, Haunted Castle, Bug, Rocket (a circular flat ride whose platform was tilted 30 degrees, Flying Scooters and Crackpot – a walk-thru dark ride, a nine ride Kiddieland. While there were few new rides added during the mid 1950s, the park did add a Hershel-built Twister ride. It was renamed Rock-n’Roll because they already had a Twister dark ride.

Olympic Park - 1962 Map

While rumors that the park would be sold to developers persisted for nearly a decade, they became a reality just after the start of the 1964 season when the park had debuted its new Wild Mouse coaster. Plans were announced for a $15 million complex of 21-story luxury apartment towers to be built on the site. The Guenthers would receive nearly $2,000,000 for the land. But on the day of the sale, when the Guenthers, principals of the Kratter Corporation, and officials from Irvington and Maplewood sat down for a luncheon to sign the papers, a mystery caller from the city government of Irvington , warned that the city of Irvington was about to change the park’s zoning from high-rise to garden apartments. The deal was postponed and negotiations between Kratter and the Guenthers came to a standstill. The park’s future was uncertain.

Olympic Park Swimming Pool

Olympic Park’s patrons got a reprieve when it was announced in April 1965 that the park would reopen in May. Guenther added a 35-foot-high sky ride that took passengers for a 1000-foot-long ride above the park and back. There was also a Trablant ride, and a paratrooper ride for children. The unpopular Air Saucers that floated on a cushion of air, installed only the previous years, were removed because they weren’t very exciting.

Kiddie Land roller coaster

Opening day on Sunday May 1st was a disaster when a crowd of 400 to 500 teenagers went on a rampage inside the park. They wrecked amusement machines in the arcade and game concessions along the midway and stole prizes. After they were chased out of the park, they attacked the nearby residential neighborhoods. It was a wild melee where household windows were smashed, and residents were terrorized. Unfortunately it frightened away patrons to Olympic Park for weeks afterwards.

Park patrons eventually returned and the rest of the season was tranquil. Bargain day Mondays, when all rides were half price still drew crowds. The circus, although cut back to two acts, also drew crowds twice daily. It was the park’s golden jubilee under the Guenther family reign, and management offered free admission to anyone over 50 years old.

Tumble Bug

Kiddie Land Boat Ride

After the season ended with Labor Day weekend, park regulars had hope that the park would continue the following season. But on Sept 23, 1965, Robert Guenther made the fatal announcement that a new buyer was found, and even if the sale didn’t materialize, the park would never reopen. The sale never happened, and the park rides were sold. Disney bought the largest carousel in the world that was later installed at Walt Disney World in Florida. The park remained empty for 13 years until 1979 when construction began on a light industrial park.

Jet Star roller coaster

Return to Lost Amusement Parks - Home Page